Scaling in Principle

This blog post was part of the event Step Into System Innovation - A Festival of Ideas and Insights on Nov 9th to 13th, 2020 and sums up the fifth webinar of the week. Watch the recorded webinar and read about the event here.

——

Anna Fjeldsted begins tackling challenges in a brilliant way, “well I don’t know how we could do that, but I’d really like to take the risk.” This was the premise with which Jennie Winhall opened our fascinating discussion, as she introduced her colleague Anna and began diving into the complexities of how to scale solutions, while ensuring those solutions stay true to their core purpose.

Above all, Anna and Jennie are interested in what it takes to be a frontline worker, how to bring about systems change from the inside and what key principles we can use to develop radically different approaches.

One participant asked, “what is most important to do in order to stay true to the original idea when scaling up?” This is where Anna and Jennie’s principles-based approach comes to the fore. They have developed a unique model of working towards systems change which is both adaptable and scalable. This all began with their work at NExTWORK, an initiative supported by the ROCKWOOL Foundation which seeks to address Denmark’s consistent problem of young, under-qualified people failing to pull themselves up onto the job ladder. NExTWORK’s radically different approach shifts power over to the young people, providing them with the opportunity to develop their own professional identity while they form genuine relationships with both the practitioners who are part of the initiatives and the companies where they are hoping to find work. Anna and Jennie stay clear of prescribed manuals which tell frontline teams how to deliver a service, and instead tap into their creativity, encourage them to claim ownership over their approach and take advantage of their resourcefulness while acting from a small set of “system-shifting” principles.

Something that was crucial to Thursday’s discussion was the idea of building “stepping stones” towards systems change. As Charlie’s diagram demonstrated, creating stepping stones provides a way for all players, both those working within the system and outside of it, to take a careful and steady approach towards bringing about fundamental change. Stepping stones, quite literally, lay down the path, they represent the process. Focussing on building stepping stones means you avoid the often daunting and unsuccessful task of trying to rapidly jump from problem to solution, which is problematic from the very get-go, as many of our speakers have spoken about throughout the week.

NExTWORK is in fact a stepping stone in itself. It is an experimentation, it is the trial of a new approach. The learning process that comes out of building these stepping stones is crucial.

For Anna and Jennie, the “system-shifting” core principles are what can provide organisations, frontline workers and municipalities the stepping stones they need to develop new, workable approaches to change. They are not instructions, they are not a vision statement. They are a tangible set of values which can be adapted to different contexts. They are angled towards the shifts and central purpose, but they are also there to fire up the imagination, so frontline workers can begin to ideate and explore new ways of doing things. Perhaps we should think of these principles as the roots of a plant, or the starter for baking bread. The principles will grow, they will expand, they can move and adapt to their external environments, but they also have the potential to produce something very different to what they started out with.

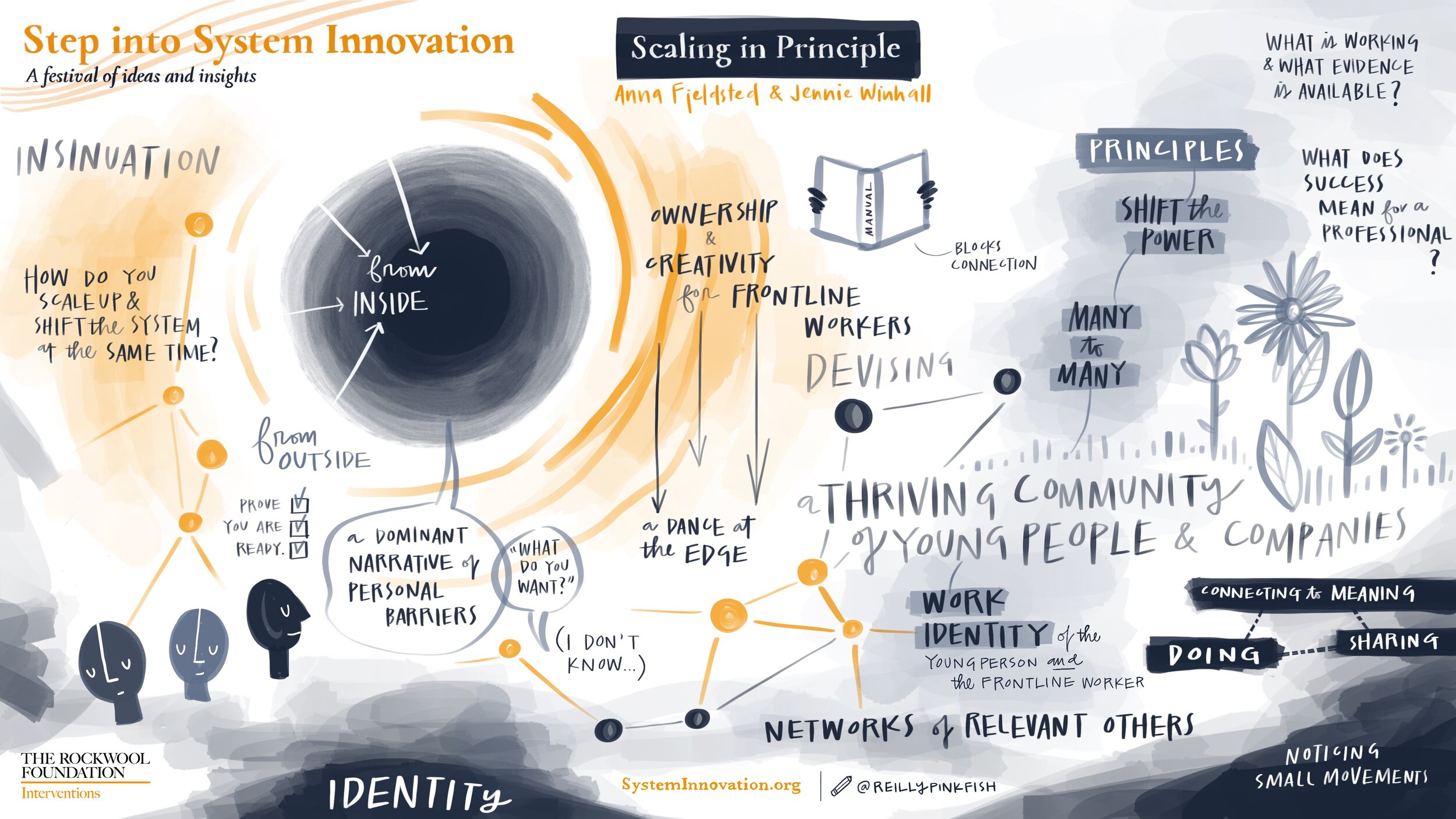

Work identity, many-to-many, shifting the power.

These are the three operating principles that Anna and Jennie use as the basis of their work. However, it is not enough just to have these principles written on a post-it note on an organisation’s office wall, team members must have an active engagement with these principles. It is not enough to think about them, you have to ensure that they help you start doing. Without actions, principles are pointless.

So, you understand and adopt these principles, and you start doing things. You take action, you implement, you plan, you create. Then, you connect these actions to meaning. As Anna explained, “principles help us connect what we do to the overall purpose.” This reminded us of something Sophie Humphreys highlighted during her own talk, which was the need to always have one eye absolutely fixed on your core purpose. If your team doesn’t have a well-defined, shared purpose from the outset, any approach you develop may crumble under systemic pressure.

The work does not stop there, however. Once you have used your guiding principles to take deliberate action which directly addresses your central purpose, you must then share your experiences with the wider system. You must be able to demonstrate your experiments with the systems you are working with and within, in order to achieve accountability and support. This is where an interesting question from one of our participants came in, who asked how you could prove the veracity of your approach based on these principles. Anna and Jennie had an intriguing answer. As well as working in a different way, you also have to develop new metrics for measuring that work. If you introduce new principles, you must also introduce new ways of measuring the outcomes. At NExTWORK, Jennie and Anna have built a monitoring system which allows them to start picking up signals of how things are changing, step by step. It is noticing these small improvements that means you can begin to show the efficacy of your approach. In regard to NExTWORK, they have already begun to see the ripple-effect that their approach has had on a broader context, as their principles-based ideology has begun taking off in other areas of municipal life.

As well as allowing us to build new approaches to change, principles also provide us with some kind of shared language. As social innovators deal with multiple players across the board, from vulnerable individuals to the frontline workers, to municipalities and policy-makers, convening with a shared understanding of these principles makes moving forward far easier.

For Anna and Jennie, another crucial benefit of this principles-based approach is that it allows for trial and error. Setting these guiding principles encourages people to feel that it is a success simply to try something out and see when something isn’t working. This focus on experimentation and learning is key. As Jennie eloquently put it, "principles give weight to a marginalised way of thinking. It helps us move away from the dominant narrative.” That dominant narrative, for a long time, has been to roll out services that supposedly provide ‘the solution’, without opening up the conversation.

Another crucial aspect of working with these principles is knowing how and when to improvise. Anna trained in theatre, and her creative background has been instrumental in the development of her approach. One participant commented on what she regards as the need for more of the arts in systems innovation. As she said, “creating new narratives and enabling experimentation is what artists do brilliantly” and that is precisely what system innovators hope to do. Anna and Jennie encourage the people they engage with to improvise, to use their imagination. Devising theatre is a practice that requires actors to invent scenarios based on a fixed set of “rules” (for example, character relationships or a broad storyline). Using those rules, actors are free to create in the way they see fit, always guided by those underlying rules.

This is exactly what Anna and Jennie hope social innovators can do using a set of guiding principles, although they accept that it isn’t enough to simply tell people to be creative, you have to provide them with the structure in which they can do that. Therefore, something Anna and Jennie also do is think about the capabilities and characteristics teams might need to be able to work with these principles, because, as Anna pointed out, “it simply isn’t enough just to have these principles, you need to be able to improvise from them.”

Devising theatre is also important for Anna because of the collaboration that it involves. As she said, “you have to take a shared responsibility” with the others that you are devising with. You need to trust your fellow actors’ ability to create. You have an idea that you want to express, and you have the principles, so you start listening to each other, and then you improvise - across theatre and systems, this is the process Anna and Jennie want to achieve.

Anna and Jennie are committed to taking the lived experience of frontline workers into consideration. One of the recurring questions of our festival has been, how can you work within the confines of a system and meet its demands while simultaneously trying to transform it? Understanding the complexity of this undertaking, Anna and Jennie set out to actively support frontline workers as they navigate through this process. For our speakers, addressing this issue is just as important as addressing those being served. This is something Sophie Humphreys and Alex Fox also touched on during their live discussion, this idea that it is essential that we build reciprocal relationships between frontline workers and the individuals in need. The practitioner must also feel satisfied with what they are doing, and if they genuinely feel they are making a difference, they will undoubtedly continue to do a good job. This is why Anna and Jennie encourage frontline staff to be creative while helping them build a sense of ownership.

NExTWORK successfully does this. In a normal job centre environment, the typical one-to-one meetings between frontline workers and young individuals looking for work aren’t just overwhelming and intense for the young people, they are also difficult for frontline workers. There is often a great deal of pressure riding on those meetings which is unproductive for all the players involved. Anna and Jennie wanted to completely reform these meetings and find out what works better for both the frontline workers and the youngsters. This is why one of Anna and Jennie’s three essential principles is “many-to-many”. In the context of NExTWORK, this means setting up meetings between groups of young people, groups of practitioners and indeed groups of companies.

This, in turn, requires reinvigorating what our notion of good work is and means, as it can’t always be measured by simply reaching goals or meeting demands. Helene Bækmark, one of our guest discussants, made a very interesting point about the need to re-establish what “success” means in the professional sphere: “we need to talk a lot about how professionals perceive their success as a professional, when do they feel they’re doing a good job”. Anna and Jennie have successfully managed to make both the professional practitioners, and those in search of a new professional identity, feel good about the process. They have managed to “bridge fear and safety”. They’ve encouraged frontline workers to take risks, to engage in creative, adaptive problem-solving, and to experiment, while remaining within the system and continuing to perform their tasks.

For the young individuals at NExTWORK, Anna and Jennie’s team have encouraged them to develop a real sense of self. They have asked the right questions, which allow the young people to build a new identity, no longer haunted by the terrifying, often unanswerable question, “what do you want to be?”

In their support of frontline teams, another fantastic thing that Anna and Jennie do is invite workers to invent not compromise. As Anna eloquently said, “it’s quite a dance there on the edge. It’s a place of tension, to meet the demands of a system and risk doing things differently, and then you have to defend what you’re doing, why you are exploring new approaches.” However, for her and Jennie, this tension is in fact key: “in that tension, you can start creating”.

One participant made an interesting comment in relation to this approach, “in my experience, it goes back to professional curiosity and capturing learning, recording, reflecting and sharing. How do we invest in this more when wanting to change systems?” This is precisely what Anna and Jennie are hoping to do with their work, by capturing not only the professional curiosity of the young individuals within the NExTWORK programme, but also that curiosity and creative capacity of the frontline teams.

Frontline workers often feel like they have to choose between the idealistic thing they’re trying to do and the story they’re being fed by the system that tells them that idealistic thing won’t work. At that stage, many people compromise. Instead, Anna teaches teams to go through a process of understanding what’s underneath the demand of the current system, what is important to it, and working out how to manage that with the new work they’re trying to do. Ultimately, you can hold both of those and find an approach that transcends the paradox, moving forward with two approaches that seem to be entirely oppositional but can in fact work alongside one another.

To finish off, I’d like to highlight one of the points made by our other guest discussant, Tim Draimin, that was picked up on by Anna, Jennie and a few of our participants. Tim spoke about the need for “the insinuation of ideas into a system”. Instead of talking about infiltration, this idea of insinuation lends the approach a new, softer, more accessible tone. The relationship between the new project and the broader context can be one of insinuation, in which this principles-based approach is gently and strategically introduced into the existing system, without raising too many alarm bells.

In order to insinuate, you must understand when tension is fruitful and productive, rather than destructive. Using “system-shifting” principles, we can be creative, imaginative and cooperative, building new and better systems for the future.