Resourcing Systems Innovation

Reframing and transform

Download

Authors

Jennie

Winhall

Charles

Leadbeater

November, 2022

1. Introduction

In Building Better Systems, we introduced four keys to unlock system innovation: purpose and power, relationships and resource flows.¹

These four keys make up a set. Systems are often hard to change because power, relationships and resource flows are locked together in a reinforcing pattern to serve the system’s current purpose. Systems start to change fundamentally when this pattern is remade so that a new configuration can emerge, serving a new purpose.

In this essay series we delve deeper into these four keys and provide practical advice on how they can be put to use. This essay is about how making new, different and better systems means creating more productive, sustainable flows of resources.

The character of economic and social systems are shaped by the resources that are critical to it, whether that is land in agrarian feudalism; factory labour and machines

in early capitalism; oil, and to a lesser extent gas, in the era of mass mobility and consumerism; knowledge, information and intangible assets such as brands in the early 21st century economy; or the role of renewables and decarbonisation in the green economy towards which societies are trying to move.

The nature of the system takes its cue from the kinds of resources that are critical to it, whether they are found fixed in the ground and extracted from it, or created fluidly in culture and grow through innovation. Different kinds of resources - whether they are extracted or created - lend themselves to different kinds of systems.

Innovation is always about how resources are used; how costs are reduced and productivity increased; how new markets, ways of life and unforeseen possibilities can be opened up. Approaches to innovation tell this story in different ways.

Incremental innovation is about doing the same things better, through small changes to the use of existing resources to squeeze out gains in productivity, quality and cost.² Disruptive innovation is about how new, low-cost technologies disrupt incumbents, disorganise industries and open up potential vast new markets for new entrants.³ Mission-driven innovation is about how public and private resources can be directed to tackle big social challenges and achieve big societal goals that would be beyond either sector acting on its own.⁴ Frugal innovators create ultra low-cost products and services, repurposing existing technologies to strip them down to their bare essentials.⁵ Open innovation is about how organisations reach beyond their boundaries to mobilise additional resources, ideas and know-how.⁶ Sustainable innovation enables the clean and seamless recycling of resources so that nothing is wasted and no pollution is left behind by the production process.⁷ Regenerative innovations renew the social and natural capital on which they draw.⁸ Social innovation is about how people can come together in new forms of organisation, movements and cultures to create better social outcomes in education, health and welfare.⁹

Stories of innovation show how resources can be economised, to cut costs and raise productivity; and how they can be mobilised, to create new possibilities for creating value, allowing people to live longer, better, and more fulfilling lives. What is distinctive about the approach that system innovation takes to how resources can be mobilised to generate better outcomes?

Why System Innovation is Different

We need to shift entire systems for the way we grow food, provide healthcare, generate energy, move around, work and consume.¹⁰ That is one reason system innovation is so critical. Systems as a whole create big outcomes, not discrete products and services within those systems.

System innovators may act on one point of a system but they do so to shift the system as a whole. That means seeing the way resources flow through whole systems, not just the parts.

System innovators take a wide view of the kinds of resources involved as they develop ways to mobilise the whole resources of the system: tangible and intangible, money and people, hard and soft, public and private, new technology and old. Far-reaching changes to systems are never just about changes to the supply side, how products and services are provided; they also arise from the demand side, and how consumers and citizens deploy the resources they have to hand to live better lives. System innovators work with the whole combination of resources available to a system across three layers.

Economic resources measured in money include: work done for wages, capital invested to make a financial return, money lent for interest, profits earned by companies and taxes paid by citizens to fund public services. This monetary layer of systems is quantifiable, with resources often traded in markets or provided by public services. One can find all kinds of financial capital at work in this layer: venture, commercial, philanthropic, public.

Social resources which elude formal measurement include: trust and reciprocity; mutual support and care; and generosity and giving which stem from our relationships in families and communities, how we look after one another across generations. Resources in the social economy are mobilised by a sense of reciprocity and are vital to many aspects of care, for children and the elderly, for example. Neighbourhoods and communities depend on the way citizens look after them, alongside the services provided by councils. Our most valued public goods - safety, health, care, learning

- depend on how citizens look after one another as well as on the formal, paid-for services provided. One can find all kinds of social capital in this layer.

Environmental, natural resources, on which social and financial systems depend, include energy, minerals and raw materials, but also environmental services which provide us with clean air and water; the biodiversity which supports food production and natural habitats.

“System innovation changes the resources that a system as a whole mobilises and deploys: their quantity and quality, productivity and cost, the energy they use, the waste they create and the ways in which they flow and interact to achieve better outcomes.”

Our work at the System Innovation Initiative is largely focused on the interaction between the economic and social layer, of reciprocity and mutual support; for example, how people assemble solutions to their care needs or find work by combining resources from the social and economic layer. All systems now need to be seen in the light of their impact upon the environmental layer of natural resources, especially their use of fossil fuels and carbon. System innovators work on the systemic linkages within these layers but also between them: how the financial, social and natural can work together to create better social outcomes.¹¹

System innovation changes the resources that a system as a whole mobilises and deploys: their quantity and quality, productivity and cost, the energy they use, the waste they create and the ways in which they flow and interact to achieve better outcomes.

The best way to explain how system innovators go about their work is to compare alternative approaches in the same setting: New York City in the 1960s.

The Battle for New York

The battle for the future of New York in the 1960s between the master planner Robert Moses and the writer and community activist Jane Jacobs is the stuff of urban legend. It’s also a case study of how system innovators mobilise resources to realise their different visions.¹²

Moses saw an opportunity to modernise the city, with wide, straight highways running between high-rise apartment blocks taking residents to work in skyscraper offices. That would allow the city to grow by making it more efficient: clean, ordered and livable, certainly compared to the tenements Moses wanted to raze. There was no room for sentiment in Moses’ vision of the future. He was the master builder and planner, power broker and system convenor, in his own eyes a transformational visionary who wanted to erase the city’s grubby past.

His vision would have driven bulldozers and expressways through many of the lower Manhattan neighbourhoods - Soho, Little Italy, Washington Park and Greenwich Village - which were dear to Jane Jacobs. Moses had a helicopter perspective; he saw the city from above. Jacobs saw it from the street up.

Jacobs was animated by a different sense of what made city life vital and dynamic: the convivial life on the street and in small public spaces that are at once cultural, commercial and civic. For Moses, a good city was a vast social machine. For Jacobs, it was an evolving social organism.

Moses and Jacobs had very different accounts of the resources needed to realise their visions.

Moses framed a picture of what modern city life should look like: clean, efficient, ordered. That frame set the city in the context of the conditions of the time: the social optimism after World War II that large scale public works could propel a leap in shared prosperity. The material conditions of rising affluence, mass production and mass consumerism, cars, supermarkets, fridges and televisions made the Moses story tangible. That framing showed how the city’s resources could flow in ways that generated increased material productivity. People would flow through the city like units of work and consumption, utility and satisfaction. The automobile was an emancipatory technology; highways were arteries of progress. Moses’ vision required vast investment of public and private capital to build new infrastructures for the modern city: roads, bridges, skyscrapers. That had to be matched by brutal disinvestment to get rid of the unproductive old city, including its old housing stock and much of the clutter of street life.

Jacobs, on the other hand, assembled a powerful coalition around an alternative vision of modern city life, one which still inspires urban designers to this day. She framed the good life around the bustling street culture that was convivial, creative and bohemian. The point of city life was not the scale of the skyscrapers and the width of the roads but the density, diversity and intensity of the social exchanges as people bumped into one another. Jacobs too framed her story in the conditions of the time: the cultural and social movements of the 1960s which promoted an ethic of bottom-up community development, later taken up in the

Danish planner Jan Gehl’s influential ideas of making “cities for people.”¹³ Jacobs came to speak for new generations of bohemian, cosmopolitan artists, designers, restaurateurs and retailers who remade the city as a place for creativity, the harbingers of the creative urban class and all the wealth it would generate. That led to a different flow of resources and, over time, a massive reinvestment to regenerate and renew the historic city fabric in lower Manhattan. New developments were threaded through old infrastructures. Moses wanted to unbundle and separate work from

daily life. Jacobs thought the city only worked by people being bundled together and mixing, in the conviliatiy of the thriving market or bustle of the busy street.

Moses and Jacobs were very different. For Moses, big government, modern corporations and new technologies were agents of progress evidenced by mass consumerism. For Jacobs, creative, mixed, urban communities were agents of progress evidenced by the vitality of life on the street. Jacobs eventually won the most obvious battle, preventing a crosstown expressway carving through Washington Square. Her warnings about Moses’ plans were borne out by the Cross Bronx Expressway which helped tip the borough into urban crisis as local businesses closed, residents departed and much of the housing stock fell derelict.¹⁴ Yet Moses also left

a legacy of parks and parkways, open spaces and urban infrastructure without which New York could not have grown.

The comparison of Moses and Jacobs highlights four ways resources shift when a new system develops: frame, flow, find and free up, as set out in the table below. Let’s look at each of these aspects in turn.

FRAMING

How will you frame how resources could and should be used?

How will that framing redraw the boundaries of the system and its relationship to wider systems of which it is a part?

MOSES

Modernist accounts of the city as 'a machine for living’.

Part of the growth of post- WWII mass production and mass consumerism, allowing change at scale.

JACOBS

Human and social account of the city as a social organism, made by relationships.

Part of the growth of the 1960s social and cultural movements for bottom-up community development, aimed at quality of life.

FLOW

How will you change the way resources flow through the system? How will demand create supply?

MOSES

Efficiency, scale, speed, productivity.

Unbundling the city to allow specialisation of work, home and leisure. Separation of functions.

JACOBS

Creative connection: intangible sociability and conviviality.

Bundling the city to allow the mixing of work, home and leisure. Combination of functions.

FIND

How will you find the spare resources needed to shift the system to a new way

of working? Will these spare resources come from outside or inside the system?

MOSES

Massive external investment in new infrastructure.

JACOBS

Regeneration from within communities to renew existing infrastructure

to maintain the fabric of social life.

FREE UP

How will you free up resources from within the system through disinvestment to create space for new growth?

MOSES

Wholesale and unsentimental demolition of the old to make way for the growth of the new.

JACOBS

Seizing opportunity to repurpose run down, written off buildings, such as warehouses.

2. Frame

Technology is not at the heart of system innovation; reframing is.

A system innovator offers a disruptive and transformational reframing of a challenge and an opportunity which allows people to see how the resources available to the system can

be reconfigured to achieve better outcomes. The framing that system innovators provide acts as a “visible attractor” for others to pour their resources into the opportunity it opens up.¹⁵⁷

Take the way that Karyn McCluskey, the police officer charged with reducing knife crime in Glasgow, helped the city tackle its knife crime epidemic.¹⁶

McCluskey reframed the city’s wave of knife crime as a public health challenge, like a virus that had to be dealt with at source, to limit its transmission. When knife crime was seen as an individual crime it was seen as an issue to be dealt with by the police and the courts. When McCluskey reframed it as if it were a disease and a public health challenge, it became the responsibility of a much wider range of players - police, social services, housing, education and employment services. That widened the range of resources that could be put into tackling the challenge and at the same time opened up much greater community-wide gains. By reframing the challenge, McCluskey multiplied the resources available to tackle it.

“By reframing the challenge and the opportunity, system innovators can reconfigure the resources available to them. That is why so many social innovators build on the capability of people and communities, rather than starting with what they lack and how public services can meet their needs.”

Much the same kind of framing challenge (and opportunity) is facing mental health services, tackling rising levels of sadness, anxiety and depression, especially among young people. If mental health is framed as an individual medical condition, to be diagnosed and treated, then it becomes the responsibility of the medical profession and hospitals. Few health systems have the resources to tackle pervasive mental health challenges this way; many specialists think this approach is not only costly but ineffective. If mental health is reframed, however, as a social and relational phenomenon, rooted in how people feel about their lives, relationships and prospects, then it can be addressed in many more ways, in many more settings. By reframing the challenge and the opportunity, system innovators can reconfigure the resources available to them.¹⁷

“System innovators frame the future so that others can invest in it. Where the imagination leads, the investment follows. The measure of their success is not the growth of their own organisation but the wave of investment by other people that they trigger.”

That is why so many social innovators build on the capability of people and communities, rather than starting with what they lack and how public services can meet their needs. Peter Block is the best known advocate of the idea that communities can create their own kinds of abundance if people can find the right ways to share and combine their resources.¹⁸ This capabilities approach, inspired in part by the work of the development economist Amartya Sen¹⁹ and the philosopher Martha Nussbaum,²⁰ is evident in Costa Rica’s extremely effective community-based primary health care system, for example, which frames health as a form of well-being created by a community.²¹ Good health is not a service to be delivered by medics once they have diagnosed an illness, but something they create with the community. Health care might be delivered by a hospital; good health is created by a community.

Technology plays a role in this story because it is one way system entrepreneurs disrupt conventional frames and provide new ones.

The economic historian Carlota Perez says that new technological and economic paradigms are announced by “visible attractors” that contain the kernel of an alternative, better system: in 1771 Arkwright’s Cromford Mill announced the possibility of mechanised textile production; in 1829 Stephenson’s Rocket opened the door to the age of steam. These were small-scale working models for an entire, alternative way of living and working.²²

To be effective, however, a “visible attractor” has to unlock the collective imagination, Perez says, by symbolising “the whole, new potential” of that system, such that it sparks the “technological and business imagination of a cluster of pioneers.”²³

In social fields like welfare, health and education, the “visible attractor” is a working model for a different kind of social philosophy, a way of seeing what people and communities are capable of.

When Richard Arkwright launched his Cromford Mill, Henry Ford opened his first factory with a moving assembly line,²⁴ Karyn McCluskey initiated her preventative approach to knife crime and Álvaro Salas prototyped his community-based health system, they were all framing the future so that others could invest in it.²⁵ Where the imagination leads, the investment follows.

The measure of their success was not the growth of their own organisation but the wave of investment by other people that they triggered. A new frame directs attention to new possibilities, excites the imagination and spurs people to action, to put their resources to use to make the picture of possibility a reality. As Carlota Perez (and many others) argue, the potential for technology can only be realised within new forms of social organisation, with new kinds of institutions and ideas. Technologies need a social vision to bring them to life.

Framing and Farming

In an essay written in the early 1950s, The Question Concerning Technology, the philosopher Martin Heidegger argued that technology was not a tool by which we achieve our ends, but a way to frame how we should live.²⁶ He used the example of a field to make his point.

A field, Heidegger argued, could be framed as: a meadow of wild flowers; a place where a farmer tends a rotation of crops; a unit of production to yield a single crop as efficiently as possible; the site for a mine to excavate the minerals below its surface. How the field is treated as a resource depends on which framing one adopts. Heidegger’s point is that resources are never neutral, objective units; what resources we see is determined by how they are framed, with different interests and world views in mind. When systems change, those frames are contested. The humble field is now at the heart of one of those contests which embodies the interplay between the financial, social and natural layers of resources we set out earlier.

One of the leading protagonists in this system-shifting story is the farmer James Rebanks, who has become a best-selling author based on his account of his family’s attempts to resist the onslaught of industrialised food production.²⁷

In Rebanks’ lifetime, farming has become an intensive, industrial, high-volume system to produce the most food at the lowest possible cost. Fields have been remade so massive machines can work them. Animals that once grazed in fields are often kept

in vast, blank sheds in which they are harvested, almost like a crop. Everything has become a unit of production, detached from the landscape and the communities they once sustained, Rebanks says. The financial layer has become detached from the social and environmental layers on which it depends.

Working from his peripheral smallholding in the north west of England, Rebanks is trying to show how the entire food system could be reframed by using old technologies and principles - rotating crops, using grazing animals to fertilise the soil, recreating hedges and coppices, allowing a river to resume its natural course through his land. Rebanks’ farm is a portal into an alternative future, a provocation to the collective imagination, a reframing of how we could work with natural landscapes to grow our food. That means noticing the small, overlooked features that are too easily written off for the sake of machines harvesting monocrops: hay meadows, wild flowers, insects, hedges, curlews making their nests in fields. In Rebanks’ circular, regenerative framing, these are among the resources of the ecosystem of which he is a part and to which he owes his living. To industrial farming, they are just obstacles to higher productivity.

Rebanks’ farm has become a “visible attractor” for an entire movement of people trying to remake the food industry to explore how to rebalance the monetary, social and environmental flows of resources:

“People win the power to set the frame by building alliances and coalitions, co-opting other organisations to commit their resources to be part of their cause.”

“Reconcile the need to produce more food than any previous generation with the necessity to do that sustainably and in ways which allow nature to thrive alongside us. We need to bring the two clashing ideologies about farming together to make it as productive, sustainable and diverse as possible.”²⁸

Shifting frames always involves contests as people propose radically different frames to tackle big challenges. When Thomas Edison proposed his new electric lighting system, he was not only opposed by the incumbent gas industry but by competitors, primarily George Westinghouse, who had an alternative path to the future.²⁹ The battle between Moses and Jacobs still echoes through current debates about the future of cities.

People win the power to set the frame by building alliances and coalitions, co-opting other organisations to commit their resources to be part of their cause. At the outset, system innovators lack the hard power of money and resources, so they have to make the most of their soft power - knowledge, values, reputations, brands - to mobilise their coalition. A “visible attractor” needs to excite the imaginations of close followers. Achieving all that is rarely, if ever, the work of a single organisation. It takes a coalition in which social movements often play a critical role in shifting the terms of debate.

System innovators are radical reframers. They disrupt dominant and conventional frames for how resources can be deployed and create alternative, transformative frames, which show the way to new, better, different systems of the future. The measure of their success is not the resources that the system innovator galvanises for their own organisation but the wave of investment by other people they trigger. The key is that framing should provide a guide for how an emerging alternative system mobilises and uses resources more effectively: the flow of resources through the system.

3. Flow

Systems are flows of resources of all kinds, mobilised repeatedly and at scale to provide outcomes that people value. Resources flow into, through and out of systems. To change a system fundamentally means changing these flows: their rate, direction and impact.

A system is in a balanced yet productive state, like a bath which is not overflowing, when there are enough resources going into the system from the tap to match the rate of flow out of the system through the plug hole. Productive systems are neither stagnant nor in a state of torrent.

Systems become dysfunctional for a wide range of reasons to do with how resources flow. They become: unsustainable when they demand a flow of resources into them that cannot be sustained; wasteful because they leak away too many resources to be sustainable; chaotic because the flow of resources is constantly perturbed; stuck because blockages mean what should be a flow of resources becomes stagnant; unbalanced because the resources flow to some parts of the system but not others who need those resources just as much; ineffective because despite resources being poured into them, what flows out of them is not enough. When these dysfunctions mount, it’s a sign that a system is in need of fundamental change. How does a different flow come about?

Our focus is on public and social systems which support people’s welfare and well- being: systems for education, training, health and care. These systems now face fundamental questions about how much resource - money, people, knowledge - should be put into these systems, how those resources are used and the outcomes they create.

Public services grew in the last century as society’s resources were mobilised at scale to create huge improvements in people’s lives, overcoming hunger, poverty, ignorance, ill health, infirmity and insecurity in old age. In European societies, these public welfare systems took different forms depending on whether they were financed from general taxation, through payments made by employees and employers, or other forms of social insurance. By and large, however, public welfare state systems went through overlapping phases of growth, from: piecemeal and patchwork developments before the Second World War, building on mutual self help; a massive expansion of education, social security and health services in the wake of that war; continued growth and expansion through the full employment, high-growth period of the 1960s in the context of the Cold War; and retrenchment and adaptation since the 1970s, to adapt these systems to the globalisation of trade, the critiques of neo-liberalism and more uneven patterns of growth.

The Danish welfare state is a prime example. By the end of the 20th century, a system that began life a century before by providing pensions for war widows, was providing an extensive platform of social support for workers and families, the old and the young, the ill and infirm. The system grew strongly in the 1950s and 1960s to counter the attractions of communism in the midst of the Cold War and then adapted to provide greater “flexicurity” for workers in the 1980s era of globalisation.³⁰

Now the changing resource context for welfare states is posing huge questions about their future: the resources they can draw upon, how they are deployed and what outcomes society seeks from them. They face challenges they were not designed for.

The ageing population threatens an inexorable increase in the resources devoted to health and social care for the elderly. That will make it more difficult to fund other services, for example in education and services for young people. The transition to a green economy will bring huge changes to patterns of work, incomes, consumption and so also to the tax base for the welfare state, which grew on the basis of an energy- intensive manufacturing and services economy. The continued spread of digital technologies is disrupting organisations and occupations, giving a new twist to long- established patterns of inequality between people and places. Digital platforms have started to reach deep into our lives, providing not only new ways to make payments and execute transactions, activities which have been core to the social security welfare state, but also providing us with new ways to learn, find work, train, and access health care. We are in the early stages of the development of a digital state.

Welfare states designed initially to help people through temporary spells of unemployment are now being asked to tackle much more deep-seated social challenges which impact family life and child development. Mass education systems that were developed in the context of a steadily growing, well-organised, manufacturing-led economy now need to prepare young people for a world of volatility, uncertainty and constant disruption. Welfare states that were primarily designed to provide people with material benefits - payments to compensate people for incomes foregone - are now tackling a wave of mental stresses, especially anxiety, sadness and depression among young people.

The international setting which sets the context for welfare states is also changing radically. Memories of the collective sacrifice of World War II are fading. Welfare states grew in the context of the Cold War and then in the era of globalisation. Whatever order there was now seems to be in jeopardy. China’s role in the world economy is rising, with uncertain consequences for the position of the US and the trading and financial systems it sponsored. Instability, conflict and climate change are feeding increased migration, which then becomes an issue of solidarity and welfare.

These shifts provide the setting in which debates about the future of welfare states will be conducted. At the heart of those debates will be questions about resources: do welfare states have enough resources to do their job? Do they use the resources they have effectively enough? Do they need to find new goals, create different outcomes?

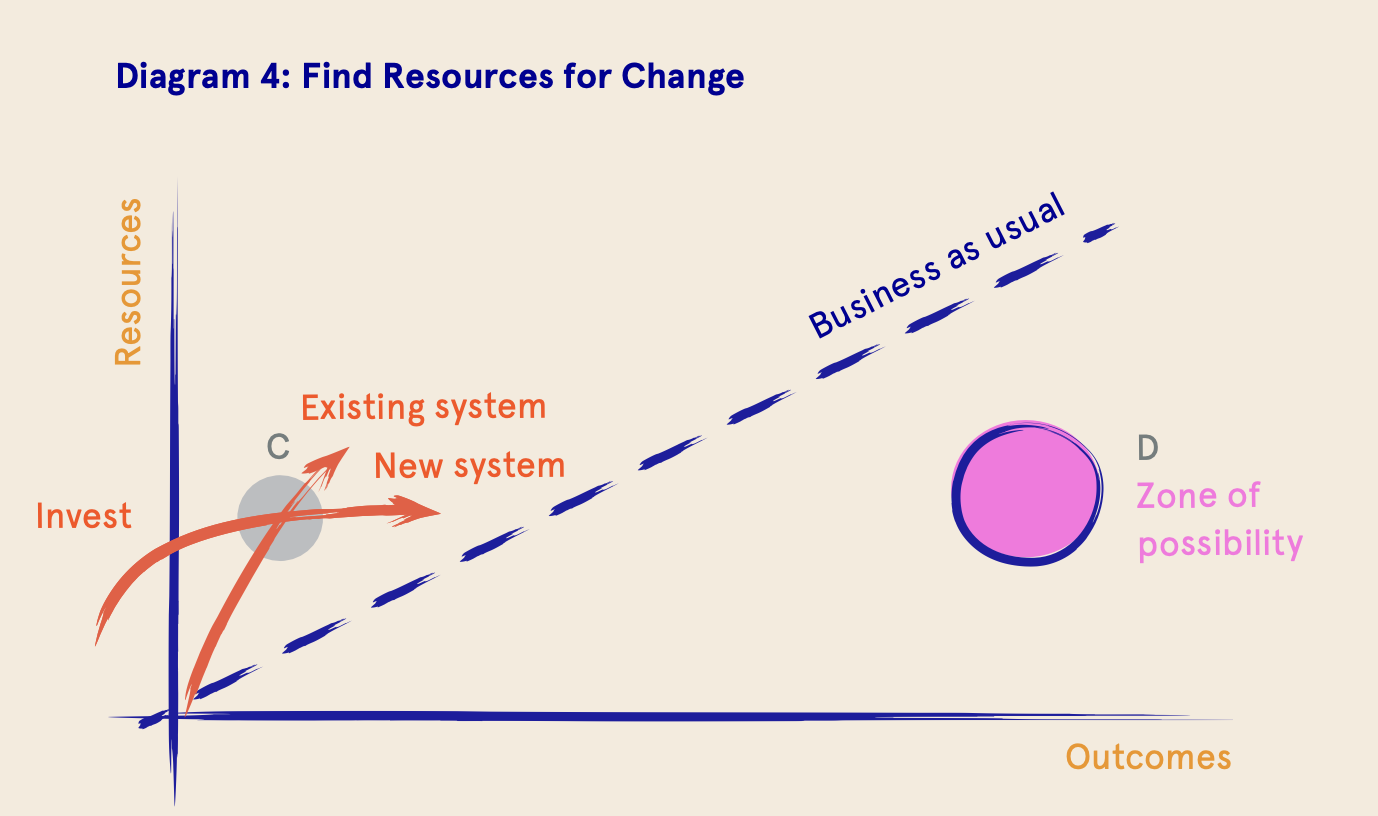

These are huge, complex questions. To make them more manageable we present three options for thinking about the future of social systems and how resources are deployed: more, better and different. Does a system need more resources? Does it need to use the resources it has better to be more effective? Does it need a completely different approach to how resources flow into, through and out of the system? These map onto three different strategies for system innovation. The diagrams below compare the three approaches by plotting how much resource a system has on the vertical axis against the kinds of outcomes it creates along the horizontal axis.

More

One approach, heard repeatedly from people working within public systems, is that they do not have the resources needed to meet the challenges they face. They need more. In many public services this is a simple equation: to get more output you need more inputs, especially more staff. On the diagram below, that creates a line rising at 45 degrees. We call this the line of ‘business as usual’. As welfare states expanded, they moved up along this line. Advocates of putting more resources into public systems to meet rising needs argue that they need to move from point A to point B. One implication is that states may need to raise taxes to fund public systems. More resources need to be put into public systems in order to generate more output.

Better

Advocates of the better approach argue that the critical question is not how much resource is put into public systems but how effectively they are used. People who take this approach point to the Baumol effect, in which public services are slower to adopt new technologies and methods and so lag behind the productivity of

the private sector.³¹ Public systems need more resources because they are not as productive and efficient as they could be. That has led to approaches such as New Public Management, which have tried to make public services more efficient by setting demanding targets for improvement.³² The hope is that by pushing systems harder to do better, the ‘business as usual’ line shifts from line A to line B, which gives a better return in terms of outputs on the resources pumped into the system. Public systems can do better with the resources they have if they organise the system to minimise waste, reduce bureaucracy and eliminate duplication, adopt new technologies and make staff more productive.

Yet experience to date shows that progress towards better is painfully slow. Simplistic fixes fail because they only address presenting symptoms of more complex, enduring, wicked problems. Endless restructuring in the name of efficiency drains morale and initiative. Services driven by prescriptive performance targets limit room for staff to find better solutions. Exacting targets can create perverse incentives: services start to hit the target but miss the point of what they are trying to achieve. This can lead to a situation in which systems have an interest in perpetuating the conditions they treat. A prime example is the way that homeless hostels rewarded for filling their beds have no incentive to find homeless people a permanent home.

Different

If providing public systems with more resources is not feasible and trying to ensure they use resources better is not enough, then the other option is to conceive of a completely different approach. This is where the reframings offered by system innovators come in.

Advocates of the different strategy argue that there is a limit to how far the tax base can rise when technology is disrupting an economy about to embark on a difficult, expensive green transition. It is difficult to see where demand for health and social care might end and so how much more resource might be needed. We cannot rely on more resources being available. Incremental innovations do not yield large enough improvements.

Advocates of more radical system-shifting strategies argue that lasting solutions to complex challenges require more collaborative, creative and relational approaches to welfare, which involve rethinking not only how resources are used but what outcomes are being sought.

System innovators attempt to design a new pattern to resource flows, which move systems far to the right along the horizontal axis, creating much better outcomes but without massive infusions of new resources, represented by point D. That space involves rethinking not just how resources are used; but more fundamentally, the mix of resources available to the system, where they come from; and the outcomes people seek from them. System innovators rethink all three at the same time. That is why their proposals are radical. To make it into that space you have to break through the heavy thick line of ‘business as usual’.

More people are proposing potentially radical changes to resource flows, for example by: radical simplification by compressing all benefits into a universal basic income; personalisation to allow clients to commission their own solutions using personal budgets; more relational welfare to help people facing complex challenges in their lives; widespread digitisation of public services to make them more personalised and more efficient at the same time; integration of siloed services, for example health and social care, to create approaches to care and well being; devolving budgets to communities to create new solutions which suit their needs. Yet more radical shifts may be required, in the context of a green transition, by circular and regenerative models of social and economic development.

System-shifting social innovators strike out across the ‘business as usual’ line to create different, better solutions.

Karyn McCluskey reframed the challenge of knife crime in Glasgow to mobilise community-wide resources to create more lasting, holistic, preventative solutions.

Álvaro Salas reframed health as well-being created by a community and to provide that he devised a community-based health care system in which medics work hand in glove with families.

In Canada, Al Etmanski reframed the position of people with disabilities, to show how they would commission far more effective solutions if they were trusted with the power to do so.³³

Alex Fox developed Shared Lives Plus solutions to allow people to care for adults with learning difficulties in their homes, as a part of their family, as an alternative to institutionalised care.³⁴

Lyndia Downie shifted the strategy of the Boston Pine Street Inn away from serving the homeless with well-run shelters to preventing homelessness, which meant working with landlords, builders and real estate developers to provide new homes.³⁵

In each of these cases, the radical solution changed both what resources were available (often creating a mix of the public and the social, the formal and the informal); how they could be used (by allowing solutions to be created more flexibly, closer to the clients); and what outcomes they sought (allowing people involved more influence over what counts as success).

To follow their lead, system innovators should ask these critical questions:

Can I change the mix of resources coming into the system, the form they take, who owns them? Often the way to increase the resources available to a system comes from changing their mix, adding the informal to the formal, self-help to professional service, the social to the financial.

Can I change how resources flow through and around the system as they are used? Can they be separated and focussed, or combined and integrated, to achieve greater effect? Can the flow be increased to prevent stagnation, redirected to places of greater need to prevent concentration or slowed down to prevent overheating?

Can I change what comes out of the system, both good and bad? Will the system become more effective with different, more ambitious goals which animate the efforts of people in the system, encouraging greater creativity and synergy?

A way to start answering these questions is to understand what is making the resource flows of the current system dysfunctional and to use that as the springboard to design an alternative which turns the problem inside out. Below we give some examples of how an analysis of negative dynamics can spur the search for positive alternatives.

4. Negative Dynamics Turn Positive

Concentration

Many market-based systems have self-reinforcing tendencies in which success begets success: the already rich have greater scope to take up new opportunities. As a consequence, resources become concentrated in certain places and social groups. The flip side of this concentration is to find ways for access to these resources to be opened up and more widely shared, to distribute and deconcentrate.

Fragmentation

Some systems are too fragmentary to be effective. Different services may each be highly efficient but they are poorly coordinated. In this case the opportunity is to find new ways to integrate and combine resources to create a more comprehensive, connected and complete service. Mothers-to-Mothers, the network that supports HIV+ mothers in Africa, works because mentor mothers connect up otherwise disconnected services.³⁶

Interconnection

On the other hand, systems can become unstable because they are too tightly connected: then a problem in one part of the system can spread quickly to others. In this case, the system needs buffers to slow down the spread of problems, the way that fire breaks slow the spread of fire in a forest.

Drift

Systems can become dysfunctional when they drift away from their goals. They can become self-serving and self-perpetuating. At their worst, systems can develop perverse incentives: the targets they seek to meet run counter to their larger goals. Shelters serving the homeless might have the perverse incentive of not wanting to end homelessness. In this case, the opportunity is to create a way for the system to adopt different, more ambitious goals. This is what Karyn McCluskey did when she restated the aims of the police in Glasgow.

Speed

Systems can become dysfunctional because they are stagnant and stuck but also because they are too fluid and fast-moving. A stagnant system is one in which resources do not flow quickly enough. The cure for that will mean opening up wider channels and clearing blockages. On the other hand, if resources are flying through a system too fast, then it might become unstable. An example might be some financial markets or even fast fashion retailing which depend on a high turnover of resources. In that case, the system may need dams and sluices to slow it down.

Redesigning Flows

Often the problem is that the resource flows of a system are misaligned with the kinds of outcomes they are trying to create. These are some of the questions that system innovators need to ask as they redesign resource flows:

Do resources need to be combined or separated?

One question is whether services need to be bundled or unbundled to be more effective. Efficient solutions are often discrete and focussed: that often involves unbundling services. Systems are sometimes stuck because they are too big,

ungainly and bureaucratic: they need to be broken down into components which

can be more efficient by being more focussed. Yet, effective solutions to complex challenges often involve integrating services that have been delivered in separate silos. That means getting different disciplines to work together, bundling up formal and informal resources, from the government and the community. Well-designed bundles of services and resources can create combinations which are far more effective, especially in tackling complex problems, than a series of efficient but poorly coordinated services.

Does the system deliver solutions or help people create them?

Aspects of health care can be delivered to a patient by a doctor. But good health is created in communities through a wide range of activities, including how people work, their diet and exercise regimes, relationships and social life. How do systems develop the capabilities of people and users to provide for themselves rather than relying on a service provider upon whom they become dependent? Creative systems are better at finding and generating resources from within themselves.

How does the system regenerate its resources?

Systems modelled on linear production lines take in resources, make something with them and deliver an output, along with any waste left over. These systems tend to

be extractive. Regenerative systems are circular. Waste from one system becomes fuel for another. One way to find extra resources within a system is to reduce waste and increase reusage. A big challenge for systems of all kinds will be to move from extractive toward regenerative models.

Does it matter how resources are owned?

How resources are owned affects how they are used. The tragedy of the commons is

a story of how collective resources, like pastures, tend to be over used when it is not clear who looks after them. The work of economist Elinor Ostrom shows that common- pool resources - like fisheries - can be well managed when they are well governed

by cooperatives, mutuals and communities.³⁷ In the 1980s, first in the UK and the US and then more widely, governments pursued policies of privatisation, in the hope

that transferring publicly owned companies into private ownership would drive better performance. Critics argue that this has often created private sector monopolies which need regulation; competition is a stronger spur to improve performance than private ownership per se. Indeed the downsides of privatisation and outsourcing, a narrow focus on profits and efficiency, are now leading some governments to bring services back within the public sector in the hope that another shift in ownership can generate better outcomes by integrating services and infusing them with a stronger sense of public purpose.

Is the aim to correct or to prevent inequalities?

The Basque region of Spain, which has high levels of cooperative ownership, is a prime example of an economy which has principles of social solidarity written into

its ownership structures.³⁸ The Basque region has the same public spending as

many other regions of Europe but with lower inequality and higher productivity. The Basque government has to spend less on redistribution because the economy is set up to generate greater equality. The economist Kate Raworth calls this approach “distributive by design”.³⁹ She argues that rather than using public services to redistribute resources, once the market has created unequal outcomes, it would

be more effective to design fairness into market systems. Business models which promote pre-distribution - for example through shared, employee ownership - create a dynamic for a fairer economy, working from the inside.

What is the role of supply and demand?

“Resources flow into systems on the supply side to allow providers to create products and services; but they also flow into systems on the demand side as consumers, users, and citizens pull the services towards them, integrating them into their lives. The most powerful change is when new forms of supply generate new kinds of demand.”

System change is never just about push from more efficient supply, it is also about pull from new kinds of demand. System innovators need to be adept at working on both sides of this equation at the same time: supply and demand, production and consumption, provision and use. Resources flow into systems on the supply side to allow providers to create products and services; but they also flow into systems on the demand side as consumers, users, and citizens pull the services towards them, integrating them into their lives. The most powerful change is when new forms of supply generate new kinds of demand. A prime example of push and pull working together is the way that postal services developed in the 19th century. Postal system innovators imagined the post would be used mainly to distribute newspapers. The system came into its own when people started writing letters to one another, an activity that mainly spread peer to peer through people emulating one another, long before children were taught to write letters at school. Often it is consumer innovation and mass changes in behaviour on the demand side which unlock the true potential of a new system.⁴⁰

System innovators cross the line of ‘business as usual’ and get into the space of possibility because they:

Find new ways to mobilise a richer, more

productive mix of resources flowing into the system.Create a more generative way for those resources to flow through the system, to mix and combine, linking new forms of provision with new forms of use and reuse.

Provide better outcomes flowing out of the system, by minimising waste and leakage and by aligning the system more closely to more demanding, ambitious goals.

It is not enough, however, for system innovators to create a compelling account of the possibility. They also have to provide a map of the journey to get there. That involves two further steps. First, they have to find the resources to propel the shift. Second, they need to show how the resources tied up in the current system can be freed up and even play a role in the creation of the new.

5. Find

To develop a system that delivers markedly better outcomes, innovators have to invest additional resources to establish that new approach. For a period, two systems will be running in parallel: an existing system and its putative alternative which

is under development. Running two systems is expensive. The

current system is likely running flat out; there are few spare resources to invest in radical change. Therefore, system innovators have to find new

resources to develop their alternative. For a time, their new solution takes the two systems combined above the line of ‘business as usual’ to point C before they can make their sharp turn towards better outcomes at point D. You first have to invest more in order to generate bigger returns later. Of course, that involves risk.

To pivot the entire system, innovators have to attract resources dedicated to bringing about change rather than making the current system work better (or for that matter, building out the new system once it is established). Let’s call these ‘resources for change’ as opposed to the ‘everyday resources’ used in running a system.

The most obvious source of ‘resources for change’ is outside investment. The economist Joseph Schumpeter said the status quo will only shift if entrepreneurs can use other people’s money to develop game-changing new business models.⁴¹ These days, risk-taking venture capital is a critical accelerant to the technological revolutions emerging from clusters such as Silicon Valley, which have produced a string of stock market unicorns.⁴² Social impact investors aim to play a similar role in social systems.

Yet external venture investment is just one resource for change.

Often the capital to develop a new approach comes from the government. From antibiotics developed in the Second World War, to the creation of public service broadcasting, the satellite systems that power GPS navigation and many of the underlying technologies of the Internet and the World Wide Web, private investment almost always depends on public support to make it effective.⁴³

“Shifting a system requires resource flows to change within and between the financial, social and environmental layers of a system.”

Philanthropists, with little interest in making market rates of financial return, can be the first to back risky social projects. The philanthropist Katharine McCormick funded the early development of the contraceptive pill.⁴⁴ Cicely Saunders created the world’s first hospice in south London with philanthropic donations.⁴⁵

In some settings, the startup capital for new approaches can come from the users themselves who are frustrated with traditional offerings. That is how the mountain bike started life.⁴⁶ Frustrated mountain bike riders started building their own bikes because traditional bikes were so deficient. Veganism started as a fringe cultural movement but it is now reshaping the mainstream food industry.⁴⁷

Bringing a new system to life depends on different kinds of investment being combined - venture capital, public investment, philanthropy and mainstream commercial investment. One of the biggest stumbling blocks to investment in new systems is the lack of effective coordination, for example, through pooled funds or an investment manager whose job it is to bring these different investors together. To be effective, investment needs to work alongside other strategies to bring about change, such as campaigning to promote new legislation or to shift consumer norms. At a larger level, investment - in the economic resources layer - needs to work with changes in the social and environmental layers.

That is why a growing field of investors - public, social, philanthropic and venture

- are seeking to create investment vehicles which bring together different kinds of capital to invest in system change. Changing economic and social ecosystems requires a parallel ecosystem of investment and finance. As we said at the outset, shifting a system requires resource flows to change within and between the financial, social and environmental layers of a system.⁴⁸

However, not all ‘resources for change’ come from outside the system. Sometimes they can come from within it as well.

The social innovation theorist Frances Westley argues that resources are “released” within systems through crisis or shock - like a forest fire - which allows the system to reorganise itself, much as foliage and trees grow back once the fire is over.⁴⁹

Once a successful new ecology emerges, it grows and consolidates, drawing resources to it and generating resources for the wider system in terms of energy and biomass. Healthy, resilient systems are always releasing resources so they can reconfigure, grow and consolidate.

Systems that are stuck and rigid never release any resources to allow change. Systems in which there is constant disruption can never settle down to grow and consolidate. System entrepreneurs, Westley argues, find ways to make the most of windows of opportunity when resources are “released”, which allow them to reconfigure the much larger flows of resources through a system.

One example of such a “release” is when resources change hands across generations. In Canada, for example, Social Capital Partners, a social impact investor, has created

a way for a generation of retiring baby boomer small business owners to pass on their business to their employees.⁵⁰ That could allow billions of dollars of wealth to be transferred to cooperatives and employee share ownership schemes, creating a fairer wealth distribution. The Good Ancestor wealth advisory service is working with rich families to transfer their wealth across generations in a way that does not deepen existing inequalities and allows younger generations to use that wealth for social good.⁵¹

Occasionally, the seeds of system innovation can come from the belly of the beast. IBM developed the technology behind the first personal computer but did not take

it forward as it was committed to mainframes.⁵² In public services, this is the prime space for ‘insider-outsiders’: people who work inside a system but can see how it would be more effective if it took a different approach. Vicky Colbert created the radical Escuela Nueva mutual self-help model of education in rural Colombia when she realised that traditional approaches to teaching and learning would not work in small rural schools.⁵³ Sophie Humphreys developed Pause, a new approach to helping vulnerable single mothers take control of their lives.⁵⁴ From her position as a senior social worker in one of London’s biggest hospitals, she could see how ‘business as usual’ was delivering repeated failure.

Creating a new system, or radically reconfiguring an existing system, is impossible without ‘resources for change’, which generally come from a combination of outside investors - public, philanthropic, venture capital, innovative consumers - and resources that are released from within systems. That means that finding ways to free up resources from within systems is also critical.

6. Free Up

Old systems do not curl up and die, even when a clearly better alternative emerges. They tend to cling on, fighting for survival. That is why creating a new system almost always requires a strategy to displace an existing one.

The displacement of older technologies and business models allows resources to be transferred from activities with low- growth potential to those with high-growth potential. It also allows our imaginations to be opened up as we jettison the intellectual baggage which comes with older approaches. Not doing so can strand innovators far from their goal: IBM did not see the potential of the personal computer it had developed because it saw the world through the lens of its mainframes and the customers who used them.

Yet the standard story is that disinvestment follows almost automatically when one set of technologies displaces another, leading to profound changes in organisations, work, consumption and wider culture. Carlota Perez argues: “Once a truly superior technology is available, with higher productivity and clear growth potential, the outcome in the medium term is practically inevitable.”⁵⁵ As profitable opportunities dry up for companies using the old technologies, they are starved of investment and eventually close. Video cassettes succumbed to DVDs, which in turn succumbed to online streaming as a way to deliver films.

However, old technologies and systems can have an enormously long half-life. The Swedish historian of innovation, Sante Lindquist, argues that at any time at least three generations of technology coexist: older technologies (like the horse and the train) find a place within a paradigm dominated by another technology (the petrol car), which is itself already threatened by an emerging technology (autonomous, electric vehicles).⁵⁶ Cinema attendance has held up well in the era of digital streaming platforms: people are spending more time watching films in more different settings.

The experience of many public service innovators is that old systems are a huge obstacle to change. With hard work, these innovators can find their way to point C in the diagram below: where they establish a new approach. Often they cannot find their way across the ‘business as usual’ line to point D, as that would require a reconfiguration of the entire system. The ‘business as usual’ line stands in their way.

System innovators need to find a way to break it down, to clear an opening for change as shown in the following diagram. Here, not only has there been a breach in the ‘business as usual’ line, perhaps due to a breakdown or crisis, but as the new alternative gains momentum it attracts resources that were tied up in the old system.

How can deliberate disinvestment happen in public systems without the disruptive power of technology and consumerism? In public systems, social norms, citizen activism and political choices play critical roles. Disinvestment has to be a collective decision, not simply the by-product of technical change.

“One way to think of system change is as a double helix of investment and disinvestment entwined together, dynamically interacting, driving one another on.”

Announcements by governments that petrol car engines will be phased out has propelled investment into electric vehicles and, as importantly, probably shifted consumer perspectives of what the future will look like. Deliberate disinvestment of this kind is often a political decision, taken as a result of shifts in popular sentiment, sometimes as a result of social movement campaigns. A contemporary example of change driven by social movements might be how the rise of veganism, vegetarianism, the ethic of “clean eating” and consumer concerns about the environmental impact of industrial food production are reshaping food systems.”

Public system innovators can develop disinvestment strategies using the four keys:

Power: Who has to cede power to allow change to happen? (For example, in professional relationships, how do social workers cede some of their power to clients?)

Purpose: How are old purposes dislodged and disinvested with meaning? For example, how do public services adopt new outcomes-based targets or how do companies shift from profit maximisation to ESG measures of value?

Relationships: How are old patterns of relationships (for example, between social workers and clients) reshaped to allow new relationships to form?

Resources: How are some resources (for example, fossil fuels) written off to allow investment in new energy sources?

All system innovation depends on collaboration. The same is true of disinvestment. Many people can play a role in it:

Policy-makers: What policy shifts need to be made to disavow old policies and adopt new ones?

Innovative consumers: How do consumers shift norms and practices, leaving old habits behind?

Insider-outsiders: How are old institutions (workhouses, mental asylums, public baths) closed down and activity shifted to other settings?

System-shifting investment needs to be matched by system-shifting disinvestment. One way to think of system change is as a double helix of investment and disinvestment entwined together, dynamically interacting, driving one another on.

7. Conclusion

System innovators are radical re-framers of how resources can be generated, mobilised and deployed. They provide new frames that show the potential for reconfiguring systems, including redrawing the boundaries of systems. At the centre of that reframing must be new flows of resources into, through and out of the system in question. It is almost never enough to attract more resources. Innovation needs to create systems and solutions that are better and different. Shifting a system requires resources for change which have to be found outside the system, in the form of investment and through the release of resources from inside the system. Additionally, innovators need to free up resources within the system to release the potential for change. Invariably, that involves disinvesting from and dismantling older systems.

This is a time when we need to act on radical ideas to reframe critical economic, social and environmental systems and the linkages between them. People are asking fundamental questions to which system innovation should offer an answer.

Should our economies be framed by the pursuit of growth in material standards of living or by environmental sustainability and well-being? Should wealth be measured in financial terms or by the quality and diversity of our shared ecology? Agrarian radicals such as James Rebanks are challenging us to rethink our relationship to the land, the animals our food comes from and the communities where it is grown. In education,

a growing movement seeks to reframe learning to create thriving well-being among students rather than focussing on results in standardised tests. Energy systems are being remade by renewable technologies. How can health systems not just cure disease but promote living well, mentally and physically?

We hope the models we have presented here help people to get started with answering questions such as these which matter so much.

8. References

Leadbeater, C. & Winhall, J. (2020). Building Better Systems: a Green Paper on System Innovation.

Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T. & Roos, D. (1990). The Machine That Changed the World. Free Press.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business School Press.

Mazzucato, M. (2021). Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. Penguin.

Radjou, N. & Prabhu, J. (2015). Frugal Innovation: How to Do More with Less. The Economist in Association with Profile Books LTD.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business Press.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House.

Winston, A. S. & Polman, P. (2021). Net Positive: How Courageous Companies Thrive by Giving More than They Take. Harvard Business Review Press.

And: Wahl, D. C. (2016). Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press.Mulgan, G. (2019). Social Innovation: How Societies Find the Power to Change. Policy Press. And: Westley, F., McGowan, K. & Tjörnbo, O. (2017). The Evolution of Social Innovation: Building Resilience Through Transitions. Edward Elgar Publishing.

The Working Group III. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (AR6). IPCC.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House.

Caro, R. A. (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and The Fall of New York. Knopf. And: Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House. And: Flint, A. (2009). Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City. Random House.

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Island Press.

L’Official, P. (2020). Urban Legends: The South Bronx in Representation and Ruin.

Harvard University Press.

Perez, C. (2002). Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of

Bubbles and Golden Ages. Edward Elgar Publishing.

McCluskey, K. (2019, July). Karyn McCluskey: How Glasgow Reduced Gang Violence

Using Science. [Video].

See, for example: the Integrated Youth Services model pioneered by the Graham Boeckh Foundation in Canada. https://grahamboeckhfoundation.org/en/what-we-do/transform-mental-health/

Block, P. & McKnight, J. (2010). The Abundant Community: Awakening the Power of Families and Neighborhoods. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Harvard University Press.

Gawande, A. (2021, August 30). Costa Ricans Live Longer Than We Do. What’s the Secret? The New Yorker.

Perez, C. (2002). Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Perez, C. (2002). Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Edward Elgar Publishing.

See the chapter on Detroit in: Hall, P. (1998). Cities in Civilization. Pantheon Books.

See: Leadbeater, C. & Winhall, J. (2020). The Patterns of Possibility: How to Recast Relationships to Create Healthier Systems and Better Outcomes.

And: Gawande, A. (2021, August 30). Costa Ricans Live Longer Than We Do. What’s the Secret? The New Yorker.Heidegger, M. (1977). The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Garland Publishing.

Rebanks, J. (2020). English Pastoral: An Inheritance. Allen Lane.

Rebanks, J. (2020). English Pastoral: An Inheritance. Allen Lane.

Hargadon, A. B. & Douglas, Y. (2001). When Innovations Meet Institutions: Edison and the Design of the Electric Light. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(3), 476-501.

Lidegaard, B. (2009). A Short History of Denmark in the 20th Century. Gyldendal.

Baumol, W. J. (1967). Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: The Anatomy of Urban Crisis. The American Economic Review, 57(3), 415–426.

Ferlie, E., Ashburner, L., Fitzgerald, L. & Pettigrew, A. (1996). The New Public Management in Action. Oxford University Press.

Etmanski, A. (2020). The Power of Disability: 10 Lessons for Surviving, Thriving, and Changing the World. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Fox, A. (2018). A New Health and Care System: Escaping the Invisible Asylum. Policy Press.

Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems Thinking for Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting Results. Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

See: https://m2m.org/

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective

Action. Cambridge University Press.Goodman, P. S. (2021, November 16). Co-ops in Spain’s Basque Region Soften Capitalism’s Rough Edges. The New Yorker.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House.

Henkin, D. M. (2006). The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America. University Of Chicago Press.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Harper & Brothers.

Mallaby, S. (2022). The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Art of Disruption.

Allen Lane.Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector

Myths. Anthem Press.

Eig, J. (2014). The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company.

Cicely Saunders International. (n.d.). Dame Cicely Saunders Biography.

Hippel, E. V. (2005). Democratizing Innovation. The MIT Press.

The Vegan Society. (n.d.). About us: History.

See, for example: https://catalyst2030.net/resources/an-investigation-into-financing-transformation/

Moore, ML., Westley, F. R., Tjornbo, O. & Holroyd, C. (2012). The Loop, the Lens, and the Lesson: Using Resilience Theory to Examine Public Policy and Social Innovation. In: Nicholls, A. & Murdock, A. (Eds.), Social Innovation (pp. 89-113). Palgrave Macmillan.

https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230367098_4See: https://www.socialcapitalpartners.ca/

See: https://www.goodancestormovement.com/

Cortada, J. W. (2021, July 21). How the IBM PC Won, Then Lost, the Personal Computer Market. IEEE Spectrum.

Leadbeater, C. (2012). Innovation in Education: Lessons from Pioneers Around the World. Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing.

See: https://www.pause.org.uk/

Perez, C. (2002). Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of

Bubbles and Golden Ages. Edward Elgar Publishing.Krebs, S. & Weber, H. (Eds.). (2021). The Persistence of Technology: Histories of Repair, Reuse and Disposal. Transcript Publishing.